Natalya Turkina (CEM Consultancy)- “Neither Naïve Nor Fatalistic: Decolonizing Mining Partnerships With Indigenous Communities in Mongolia and Australia” published in Business & Society

Abstract

Mining partnerships have often been promoted as opportunities for meaningful collaboration between corporations and Indigenous communities. However, these partnerships frequently lack a nuanced understanding of the colonial assumptions that underpin power imbalances and divergent perspectives. This study addresses this gap by examining how a multinational mining corporation, Indigenous communities, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) representing these communities (de)legitimize their mining partnerships within the framework of global stakeholder colonialism in Australia and Mongolia. The study shows how stakeholder colonialism coerces Indigenous communities into accepting a social reality where mining is inevitable, either with or without partnerships. This dynamic reflects the hegemonic power of mining corporations, which is sustained not by a balance of coercion and consent but by discursive coercion without consent. This implies that there is a failure of this hegemonic power to fully establish itself, opening the door for subaltern resistance and counter-hegemonic struggles by Indigenous peoples. By highlighting Indigenous perspectives that challenge the prevailing managerial views in mining corporations, this study disrupts the corporate narrative that portrays the sole social objectivity where mining is inevitable. Instead, it advocates for a more nuanced understanding that goes beyond a simplistic view of mining partnerships as either naïve democratic deliberation or fatalistic stakeholder colonialism.

In many countries, mining corporations establish partnerships with Indigenous communities—groups whose identities are deeply intertwined with the lands often targeted for mining (Murphy & Arenas, 2010; Sawyer & Gomez, 2008). These partnerships are intended to mitigate the adverse impacts of mining, such as economic stagnation, poverty, and environmental degradation, thereby securing community support for mining operations (Auty, 1993). Industry proponents (e.g., International Council on Mining and Metals, 2015) often tout these partnerships as a best practice of stakeholder (i.e., rights holders, Salmon et al., 2023) engagement, designed to empower Indigenous communities as “preferred development partners” (Howitt, 1998).

Conversely, management scholars critique such partnerships as superficial, arguing they often serve as tokenistic corporate social responsibility (CSR) gestures rather than meaningful engagements (Bastien et al., 2023; Derry, 2012; Newenham-Kahindi, 2011; Salmon et al., 2023). Indeed, managers frequently overlook Indigenous perspectives, lacking genuine recognition of their belief systems and narratives (Calvano, 2008; Davidson-Hunt & Berkes, 2003). As a result, despite good intentions, corporations often perpetuate colonial legacies, creating discordant relationships that hinder genuine conciliation and harmony (Ramirez et al., 2023).

This study addresses the gap in understanding the colonial assumptions underlying power imbalances and differing perspectives on mining partnerships (Banerjee, 2000, 2022; Banerjee et al., 2021; Maher, 2019; Ramirez et al., 2023). It examines how a multinational mining corporation, Indigenous communities, and their non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (de)legitimize these partnerships within a broader discourse of “stakeholder colonialism” (Banerjee, 2000), which normalizes land exploitation, rationalizes mining as a primary development opportunity, and mythologizes corporate governance as democratic engagement. By highlighting alternative Indigenous perspectives, this study challenges the corporate narrative of the sole social objectivity where mining is inevitable.

The study argues that mining partnerships should not be simplistically categorized as either naïve win-win democratic deliberation or fatalistic win-lose stakeholder colonialism. Instead, it proposes two “arenas” (Latour, 2004)—organizational and institutional—where mining corporations and Indigenous communities can explore more equitable partnership options. This approach aims to move beyond the status quo, where mining is seen as inevitable, to a new paradigm where mining is not a foregone conclusion.

The article is structured as follows: The next section reviews perspectives on mining partnerships, discussing how Indigenous perspectives can enhance these partnerships and identifying theoretical gaps to be addressed. The research design section details the context, case selection, limitations, data collection, reflexivity, and data analysis. The findings section presents strategies used by the mining corporation and Indigenous stakeholders to (de)legitimize partnerships, illustrating their entrenchment in stakeholder colonialism. Finally, the discussion section explores the study’s theoretical contributions and generalization, concluding with final remarks.

Theoretical Perspectives

Mining Partnerships as Naïve Democratic Deliberation

Mining partnerships, often framed as cross-sector partnerships (CSPs), are collaborations between mining corporations and organizations representing Indigenous communities. These partnerships aim to protect or obtain resources that neither party could achieve alone (Newenham-Kahindi, 2011; Sethi et al., 2011; Sloan & Oliver, 2013). For mining corporations, these partnerships can offer legitimacy—defined as acceptance by their social environments (Dowling & Pfeffer, 1975)—and provide expertise in generating and distributing public goods to enhance competitive advantage, CSR, or social license to operate (Ashraf et al., 2017; Dacin et al., 2007). In contrast, organizations representing Indigenous communities, such as NGOs, seek financial, informational, and human resources to ensure the provision of public goods, including environmental protection, public health, education, and poverty alleviation (Sagawa & Segal, 2000; Yaziji & Doh, 2009).

This resource-dependence perspective on mining partnerships assumes that even with power imbalances, these partnerships are resilient once established. Despite potential misalignments in goals—such as NGOs prioritizing social or environmental investment while corporations focus on profit maximization—CSPs are more likely to endure when partners’ values, goals, and practices are relatively compatible, and resource dependence is relatively low (Ahmadsimab & Chowdhury, 2021; Prashant & Harbir, 2009; Vurro et al., 2010). Furthermore, even with high incompatibility, the strategic and pragmatic interests in sustaining the relationship often lead to the survival of these partnerships (Ashraf et al., 2017).

CSPs, therefore, are seen as a form of flexible, collaborative, and hybrid governance that allows for public consultation, increasingly adopted by corporations to engage more effectively with their stakeholders (Burchell & Cook, 2013; Seitanidi & Crane, 2009; Selsky & Parker, 2005; Van Tulder et al., 2016). However, this perspective is somewhat idealistic” as it assumes that organizations always achieve win-win outcomes in CSPs. As Selsky and Parker (2010, p. 33) ask, “Why else would actors partner but to gain synergies that would otherwise be unavailable?” Consequently, CSPs are often portrayed as extensions of democratic deliberation (Scherer & Palazzo, 2011), where consensus is reached through a deliberative process of open and fair exchange of arguments, aiming to neutralize power relations between partners (Dryzek & Stevenson, 2011). Thus, this perspective argues, while significant power imbalances may exist, these should not prevent fair, inclusive, and effective collaboration (Selsky & Parker, 2005).

In the context of increasing recognition of Indigenous rights worldwide, mining corporations must seriously consider the traditional values and customs of Indigenous communities to gain and maintain legitimacy. Yet, management scholars have acknowledged that Indigenous communities often lack the power for collective action and the resources necessary for effective deliberation in forming win-win mining partnerships (Kapelus, 2002; Yakovleva et al., 2023). Understanding how to engage in more participatory, democratic stakeholder management approaches is, however, “not always easy for an industry that historically has not set participation with diverse actors with different ideologies as a top priority,” given that mining corporations have typically wielded the power to implement community development policies that allowed them to focus on their core business—mineral extraction (Kapelus, 2002, p. 287).

In response to growing societal concerns and stakeholder expectations for ethical corporate behavior, alongside increasing Indigenous legal demands to be recognized as primary stakeholders (Olabisi et al., 2019), mining corporations have begun developing more consultative and participatory relationships with Indigenous communities over the past decade (Imbun, 2007). These relationships include CSPs and multistakeholder partnerships (Salmon et al., 2023; Sethi et al., 2011; Sloan & Oliver, 2013). However, for corporations to promote positive impacts for Indigenous stakeholders, their engagement with Indigenous communities must be “consistent with their wishes and needs as they [Indigenous communities] perceive them” (Lertzman & Vredenburg, 2005, p. 239). This is crucial because while Indigenous peoples may be interested in non-Indigenous partnerships, these partnerships may be primarily guided not by economic rationales but by their values and worldviews concerning their environmental, spiritual, and socioeconomic well-being (Lai & Nepal, 2006; Salmon et al., 2023).

Mining Partnerships as Fatalistic Stakeholder Colonialism

Despite corporate attempts to incorporate Indigenous values and worldviews in their engagement initiatives, these efforts have often been criticized as practices with a “colonial legacy”—the enduring effects and influences of colonial rule in postcolonial contexts, which continue to impact political, social, economic, and cultural structures, leading to persistent inequalities, cultural assimilation, and the perpetuation of institutional frameworks established during the colonial period (Gregg, 2019). A postcolonial perspective on CSR, therefore, posits that partnerships with Indigenous communities are not merely characterized by power imbalances that can be neutralized or managed; they are sites of hegemonic domination (i.e., coercion and creation of a cultural consensus that legitimizes and perpetuates the power of the ruling class, Gramsci, 1971), where state and market actors perpetuate the colonial legacy in relationships between corporations and Indigenous peoples (Banerjee, 2022).

CSR in this context is seen as a form of organizational neo-colonialism—renewed practices of economic, cultural, or political influence by market and state actors over regions where Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities live. Being part of the Western paradigm of management, partnerships with Indigenous communities within a broader CSR agenda represent a neo-colonial “rights discourse” (Ehrnström-Fuentes & Böhm, 2023; Quijano, 2000). This discourse, while ostensibly granting rights to subaltern subjects (e.g., Indigenous communities), often refuses their agency by ignoring their modes of organizing, deeming them incompatible with or inferior to Western ways of thinking (Bastien et al., 2023). Consequently, CSR allows the continuation of the “colonial legacy” of representation, development, domination, and control (Adanhounme, 2011; Khan & Lund-Thomsen, 2011) in various forms of neo-colonial stakeholder engagement, particularly within the context of globalized neoliberal capitalism (Özkazanç-Pan, 2019).

Instead of recognizing Indigenous peoples as primary stakeholders, mining corporations often misrepresent Indigenous communities as “fringe” stakeholders—disconnected, invisible, and in need of development by these corporations, which perpetuates the colonial mind-set of seeing Indigenous peoples as incapable of autonomy (Banerjee & Prasad, 2008; Hart & Sharma, 2004; Jackson, 2012; Kamoche & Siebers, 2015; Murphy & Arenas, 2010). Postcolonial scholars describe this approach as “stakeholder colonialism” (Banerjee, 2000, p. 27), where neo-colonial practices further marginalize Indigenous communities by depriving them of their resources and rights “to be heard and believed” (Derry, 2012, p. 261). The focus of postcolonial studies is thus on destabilizing “the hegemony of Western management thinking” (Muhr & Salem, 2013, p. 66) by recovering Indigenous perspectives that have been historically marginalized (Tinsley, 2022).

Prior research has documented the ongoing struggles of Indigenous communities against mining development projects, revealing how resistance arises in response to systemic inequalities perpetuated by corporate and state actors (Banerjee, 2000, 2008, 2011; Ehrnström-Fuentes, 2016, 2020; Misoczky, 2011; Özen & Özen, 2009; Ramirez et al., 2023; Urkidi, 2010). These struggles are rooted in the duality between the disembeddedness of Indigenous communities from their traditional ecological, economic, and cultural spheres and the embeddedness of corporations in internal colonialism—systemic dominance within a nation-state characterized by economic exploitation, political marginalization, and cultural suppression, mirroring colonial dynamics. Internal colonialism is present in both settler colonies like Australia and Canada and economically developing postcolonial mining countries in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, where state and market actors reinforce colonial legacies through ongoing modes of extraction (Banerjee, 2000, 2008, 2011, 2022; Banerjee et al., 2021).

The ongoing struggles between Indigenous communities and mining corporations represent, as postcolonial scholars argue, a failure of democratic deliberation (Banerjee, 2022). More fundamentally, these situations highlight the incommensurability of interests, where one party’s gain (e.g., land use for mining) is the other’s loss. Consequently, the legitimacy of mining partnerships cannot be formed or sustained through genuine deliberation but instead represents a form of “fabricated consent” where consensus, even if reached, remains hegemonic (Ehrnström-Fuentes, 2016, p. 435; Mouffe, 1999). For instance, some mining partnerships with Indigenous communities in Canada have been shown to “obscure and normalize processes of environmental racism, oppression, and violence” (Banerjee, 2022; Preston, 2013 p. 43).

Incorporating Indigenous Perspectives in Mining Partnerships

Given the deep-rooted issues of stakeholder colonialism and the failures of democratic deliberation highlighted above, incorporating Indigenous perspectives becomes not just an ethical necessity but a critical step toward challenging and transforming the hegemonic structures that perpetuate colonial legacies in mining partnerships. Indigenous place-based perspectives and knowledge systems, although distinct from Western “scientific” frameworks, offer invaluable insights (Berkes & Berkes, 2009; Salmon et al., 2023) into sustainable practices (Cannarella & Piccioni, 2011), local governance (Miller et al., 2015), and environmental stewardship (Mercer et al., 2010). These perspectives are not merely supplementary but are essential for creating equitable partnerships that recognize and respect the sovereignty and agency of Indigenous communities.

However, mining corporations often lack awareness or deliberately disregard these perspectives, continuing to perpetuate colonial legacies of discordant relationships (Ramirez et al., 2023). Corporate managers, in turn, remain relatively unaware of how Indigenous perspectives differ from their corporations’ perspectives, lacking genuine recognition of Indigenous belief systems, metaphors, and alternative narratives (Calvano, 2008; Davidson-Hunt & Berkes, 2003). This study seeks to address this gap by exploring the differences in perspectives on mining partnerships between corporations and Indigenous communities and examining how these perspectives are embedded in stakeholder colonialism. By understanding and integrating Indigenous perspectives, there is potential to move beyond the win-lose dynamics of current mining partnerships toward a more just and equitable framework for engagement.

Research Design

Context

To fill the above gap, I conducted a qualitative comparative case study examining how a large mining multinational corporation (MNC; hereafter Big Mine1) formed two mining partnerships with Indigenous communities in Australia and Mongolia. This study is part of a broader research project exploring how societal-level institutions shape Big Mine’s responsibilities toward local communities and the resulting contestations. Mining corporations, including Big Mine, have operated in the Australian region since the 1960s and in the Mongolian region since the 2000s. Both regions host Indigenous communities located near or around Big Mine’s mining operations. The Australian mine is wholly owned by Big Mine, while the Mongolian mine is a joint venture where Big Mine operates the project (hereafter Project Y) and retains a majority ownership stake in the project’s decision-making.

During the study, the global mining sector was experiencing a downturn, with commodity prices having fallen since 2010 (The Guardian, 2015). This downturn led to reduced expenditure on communities affected by mining operations, intensifying discussions about corporate responsibility toward local communities and partnerships with Indigenous communities. At the time of fieldwork, both mining partnerships had already been finalized, with no scope for future amendments. Therefore, this study focuses on the retrospective perspectives of both Big Mine and Indigenous communities and their NGOs regarding the period before the partnerships were signed, acknowledging that power dynamics may have evolved since.

The Australian partnership was a Land Use Agreement between Big Mine and an Aboriginal NGO representing Indigenous landowners, signed under the Australian Native Title Act 1993 shortly before this study was conducted. This partnership established Big Mine’s provision of long-term monetary and non-monetary benefits for the Indigenous community and the Traditional Owner Group, recognizing their native title rights over the land.

It is important to note that Indigenous communities in Australia face significant challenges concerning land and resource rights due to the limitations of the Australian native title legislation. Although the native title regime provides some recognition and protection for Indigenous land rights, it does not grant Indigenous communities a definitive veto power over mining projects. Under the Native Title Act 1993, mining corporations can proceed with mining activities even if Indigenous communities refuse to negotiate. This legislative framework prioritizes economic development over Indigenous land rights, undermining the international legal principle of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) as outlined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), to which Australia was a signatory at the time of the study. In addition, Australia had not ratified the International Labor Organization (ILO) Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No. 169), which sets out comprehensive rights and protections for Indigenous and tribal peoples, at the time of the study. This study aims, among other goals, to capture a better understanding of the voices of Australian Indigenous communities, whose interests are not fully protected by the Native Title regime (Chowdhury, 2023).

The Mongolian partnership was a Cooperation Agreement between Big Mine and local state authorities representing local communities, including Indigenous herders, signed under the 2006 Mongolian Minerals Law shortly before this study was conducted. This partnership secured Big Mine’s commitment to long-term sustainable socioeconomic development and employment for local communities, acknowledging its exploitation of mineral resources in the region.

It is important to note that the Mongolian government does not recognize nomad groups as Indigenous communities and, as such, they are not protected under the international legal principle of FPIC as outlined in the UNDRIP, to which Mongolia was not a signatory at the time of the study. In addition, Mongolia had not ratified the ILO Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 (No. 169) and thus was not legally committed to its specific obligations and standards. Consequently, no specific branch of the Mongolian government addresses ethnic and Indigenous peoples’ concerns. The Mongolian government treats its citizens as socially and culturally homogeneous and does not support policies recognizing Indigenous peoples (Asian Development Bank, 2020). As a result, the nomad communities affected by Big Mine’s project were not entitled to consultation or a right of refusal regarding the project’s development. This study, among other goals, aims to “politically represent” (Jack & Westwood, 2006) the nomad groups in Mongolia as Indigenous peoples, whose identity is rooted in a historically contingent, complex, and relational experience with the land (Murphy & Arenas, 2010; Sawyer & Gomez, 2008).

The differences and commonalities between the two contexts and partnerships are summarized in Table 1.

Rationale for Case Selection

The rationale for employing a comparative case study design extends beyond mere data availability, which was the case in the first place, to the essence of revealing nuanced theoretical insights that might have remained latent within a singular case analysis. These two distinct cases offer an opportunity for an in-depth investigation of a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context (Yin, 2009). The selection of these cases was strategically guided by light theorization—an initial but plausible account of contextual similarities between the cases, which may reveal “cross-cutting patterns or demi-regularities” (Kessler & Bach, 2014, p. 172). Specifically, both countries share postcolonial legacies and have strategically important mining sectors.

First, despite their differing historical trajectories, both Mongolia and Australia grapple with postcolonial legacies, including the marginalization of Indigenous cultural identities, land dispossession, and challenges in preserving heritage amid modern development. Australia, as a settler colony, experienced significant colonialism under the British Empire, leading to the displacement and oppression of Aboriginal communities, with ongoing struggles for their rights and recognition (Banerjee, 2000, 2008, 2011). Conversely, Mongolia, although not a settler colony, experienced a distinct form of colonization under the Soviets, which caused political and socioeconomic upheavals affecting the Indigenous population and traditional ways of life (Myadar, 2017; Sneath, 2003).

Second, both economically developed Australia and economically developing Mongolia rely on the mining sector, which is strategically important for their governments (Butler, 2010; Rossabi, 2005). In Australia, the mining sector is a significant driver of economic growth and export income, contributing approximately 7% of gross domestic product (GDP), with some states contributing more than others at the time of this study (Australian Government, Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, 2016). In Mongolia, mining also plays a crucial role in economic development, contributing about 20% of GDP at the time of this study (World Bank, 2018). Since the early 1990s, following the collapse of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) and the onset of liberal market-based reforms, Mongolia has become an attractive investment destination for many Western mining MNCs, including Big Mine (Cane et al., 2015).

These parallels aimed to explore whether theoretical explanations and patterns observed in one case also manifest in the other, potentially enabling theoretical generalization applicable to similar multinational mining corporations and their partnerships with Indigenous communities across both economically developed and developing mining countries. However, it is crucial to clarify that, like other postcolonial studies (Banerjee et al., 2021), this study does not intend to present Indigenous communities across these countries as identical or homogeneous. Instead, it captures and interprets subjective experiences, paving the way for replication logic to establish the theoretical generalizability of the proposed explanation across these distinct cases.

Limitations

While I interviewed a broad range of individuals and analyzed various documentary sources to triangulate the interviews, I acknowledge that I could not access all evidence universally nor directly observe the events and actions relevant to the situations examined. Instead, I relied on the retrospective recollections of interviewees and accepted these recollections at face value. Although I juxtaposed the perspectives of Big Mine and Indigenous communities and their NGOs on mining partnerships, I recognize, like other postcolonial scholars (Ehrnström-Fuentes, 2016), that there are more nuanced interpretations of how realities are constructed by these social actors.

Data Collection

The primary data sources for this study were 48 formal semi-structured in-depth interviews. Twenty-five interviews, including three follow-up interviews, were conducted in Mongolia during a 3-week fieldwork trip in August 2015, and 23 interviews were conducted in Australia during a 3-week fieldwork trip in September 2016. Each interview lasted, on average, 1 hour and was digitally recorded and fully transcribed. Five interviews in Mongolia were conducted with the assistance of a Mongolian-English interpreter, while the remaining interviews were conducted in English. Forty-four interviews were conducted in person, and four interviews (two in Mongolia and two in Australia) were conducted via phone or video call. The initial sample of interviewees was generated using a “snowball sampling” (Biernacki & Waldorf, 1981) approach, with referrals made by the first interviewees. Concurrently, public reports and media mentions of Big Mine’s interactions with local communities were analyzed to identify relevant interviewees outside of the snowball sample.

I interviewed top- and middle-level managers and specialists in community engagement from Big Mine in both countries, as well as representatives (i.e., directors, managers, advisers, experts, and specialists) of Aboriginal, herders’, developmental, and lobbying NGOs, local and state government authorities, community consultancies, industry experts, financial investors, and community representatives in both countries. In addition, I interviewed representatives of an international financial organization that co-financed the Mongolian Project Y, the Mongolian mining industry association, a holding company that co-owns the Mongolian Project Y, and an Australian trade union. Alongside the 48 formal interviews, I conducted 10 informal, impromptu conversations with community, industry, and federal government representatives regarding Big Mine’s partnerships with community NGOs and local governments in Australia (6) and Mongolia (4). This mix of interviewees and conversations ensured multiple perspectives, including both expert knowledge about the researched mining partnerships and practical reflections on how these partnerships evolved “on the ground” (Pawson & Tilley, 1997). The primary data used for the analysis and secondary data used for triangulation are presented in Table 2.

The interviewees were asked to comment on the following :

a. their understanding of Big Mine’s responsibility towards local communities and how it should be practiced;

b. examples of interactions between Big Mine and other organizations or individuals in realizing this responsibility;

c. resources used or acquired by Big Mine and those organizations or individuals during these interactions; and

d. social norms and values (e.g., community, government, religion, profession, market, corporation, family) that informed these interactions.

After each interview, I made notes to record my ideas and reflections on the interview. This helped identify key interactions of Big Mine with other organizations or individuals that most interviewees commented on—specifically, mining partnerships between Big Mine and local communities and organizations advocating for these communities—and plan subsequent interviews to explore these interactions in more detail where possible. In the Appendix, I include a note that became a major impetus for this study’s postcolonial theorization of mining partnerships. It reads: “Company people believe in the business case. Now, we live in a status quo, Western philosophy-driven society, where money is power.”

Reflexivity

During my data collection, I practiced reflexivity, understood as the “conscious and consistent efforts to view the subject matter from different angles and avoid or strongly a priori privilege a single, favoured angle and vocabulary” (Alvesson, 2003, p. 25). This involved encouraging interviewees to explain in detail their perspectives, even if I had prior knowledge, and reassuring them that my research was not funded by corporate interests. I chose interview locations based on their preferences to build trust and asked them to explain terms in their own words to avoid reliance on cultural scripts. In addition, I used various channels to reach interviewees, ensuring a diverse representation of voices, and emphasized the confidentiality of their responses.

However, beyond these methodological strategies, my positionality as a researcher also deeply influenced the study. As an early career scholar and a non-Mongolian and non-Australian (Russian speaking) researcher, my interactions were inherently shaped by my outsider status. This positionality raised issues of “epistemic coloniality” where my initial approach risked perpetuating colonial perspectives by treating local communities as homogeneous groups. Initially, I did not fully account for the distinct experiences and voices within Indigenous communities, instead merging them with other local community stakeholders. Over time, through critical reflection, I developed an awareness of these biases and sought to incorporate “oppositional views” (Chowdhury, 2023) into my analysis. This process involved recognizing and addressing the power imbalances inherent in the research, particularly how my own background and the globalized academic context might influence the representation of marginalized voices. I approached my research with a normative agenda, aiming to understand and improve the corporate practices affecting local communities. However, I had to continuously challenge my assumptions and remain “politically reflexive” (Abdelnour & Abu Moghli, 2021), acknowledging that my work was not value-neutral but rather a situated practice that carries its own set of ethical and political implications.

Data Analysis

To analyze the data, I adopted Fairclough’s (1992, 2005, 2013) Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), which offers a holistic approach to examining micro-level texts used in various perspectives on mining partnerships, meso-level discursive practices of production, distribution, and consumption of these perspectives, and macro-level social contexts that embed these perspectives. Fairclough’s CDA is critical realist in nature, meaning it primarily focuses not on individual actors and their texts but on their socially embedded relations. CDA, therefore, cannot be limited to the analysis of texts as the only object but should extend to the analysis of complex relations between actors’ texts, interactions, and higher-level social contexts that embed these elements (Fairclough, 2005, 2013).

I employed Fairclough’s CDA to interpret the perspectives (i.e., micro-level texts) of Big Mine and Indigenous communities and NGOs representing and advocating for these communities on mining partnerships during their interviews with me (i.e., meso-level discursive practices) and then explain how these perspectives are embedded in stakeholder colonialism (i.e., macro-level social context). The analysis involved a critical realist retroductive (i.e., abductive2) movement between theory and empirical data, which is underpinned by the premise that a theory should arise from the empirical data. This approach means that the researcher relies on existing theories in their analysis, thus not discovering them in the data but rather elaborating them based on the data (Belfrage & Hauf, 2015; Fletcher, 2017). I followed the iterative coding steps below using the software programs Nvivo and Microsoft Excel.

First, from the initial reading of the interviews, I selected two groups of key interviews—those with Big Mine’s representatives and those with Indigenous communities and NGOs representing or advocating for these communities—to assign one or more micro-level descriptive codes to each interview passage, ranging from one to several sentences. The codes reflected my perception and interpretation of the passages but were derived from the interviewees’ vocabularies, unveiling critical elements of their meaning systems. I then contrasted the constructed codes to cluster them into groups of first-order codes, such as, for example, statements by Big Mine’s representatives in Australia and Mongolia that mining partnerships can only minimize but never eradicate the damages of land exploitation because mining is economically inevitable in both countries. I also triangulated the key interviews with secondary data and interviews with other interviewees who commented on Big Mine’s relationships with Indigenous communities.

Second, I applied the (de)legitimization strategies developed by van Leeuwen and Wodak (1999) and extended by Vaara and Tienari (2008, added normalization) to interpret my interviewees’ perspectives on mining partnerships. I unpacked their use of language to create a sense of (il)legitimacy of their mining partnerships. There are five generic (de)legitimization strategies: authorization (i.e., reference to an authority, such as tradition, custom, or law, which gives credibility to actions or phenomena), rationalization (i.e., reference to the utility of actions or phenomena based on taken-for-granted knowledge), moral evaluation or moralization (i.e., reference to values that provide the moral basis for [de]legitimization of actions or phenomena), mythopoesis, mythologization, or narrativization (i.e., reference to stories or constructing narrative structures to relate actions or phenomena to the past or the future), and normalization as a separate category of authorization (i.e., reference to actions or phenomena as “normal” or “natural”).

Referring to these generic (de)legitimation strategies, I constructed meso-level second-order themes to interpret micro-level descriptive first-order codes as more abstract statements about strategies used by my interviewees to either legitimize or delegitimize mining partnerships. For example, first-order codes describing statements by Big Mine’s representatives in Australia and Mongolia that mining partnerships can only minimize but never eradicate the damages of land exploitation because mining is economically inevitable in both countries were coded as the second-order theme (legitimization strategy) “Partnerships as normalizing land exploitation.” First-order codes describing statements by Indigenous communities and NGOs representing or advocating for these communities that mining partnerships cannot stop mining as mining corporations are granted de facto legal clearance to exploit their lands were coded as the second-order theme (delegitimization strategy) “Partnerships as the absence of denormalizing land exploitation.”

Third, I turned to Mudimbe’s (1988) three characteristics of colonialism—the domination of physical space, the incorporation of local economic histories into the Western perspective, and the reformation of the natives’ minds—to provide a macro-level explanation of how second-order themes interpreting my interviewees’ (de)legitimization strategies are linked to the higher-level effects of stakeholder colonialism, which embeds these strategies. For example, I grouped the second-order theme “Partnerships as normalizing land exploitation,” which interprets Big Mine’s legitimization strategy, with the theme “Partnerships as the absence of denormalizing land exploitation,” which interprets the delegitimization strategy by local communities and NGOs, into a third-order aggregate category explaining these two second-order themes as the domination of physical space, coining it as “Normalized land exploitation.”

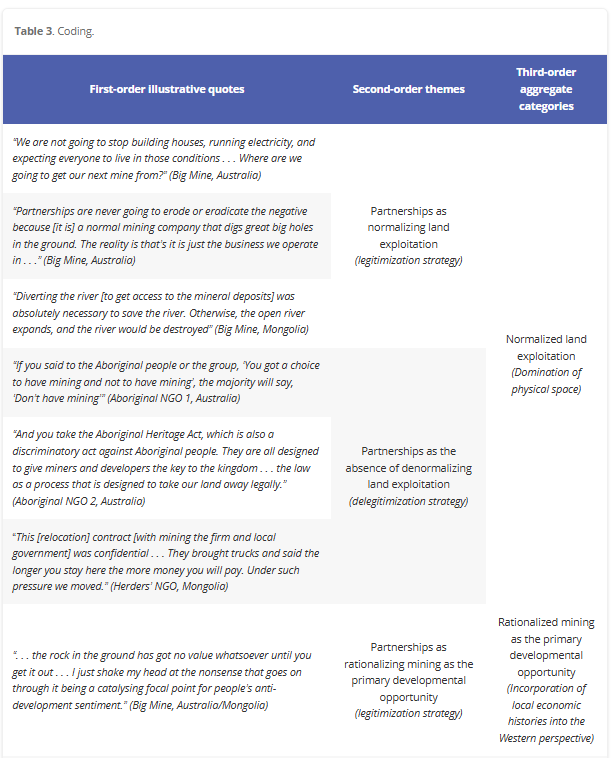

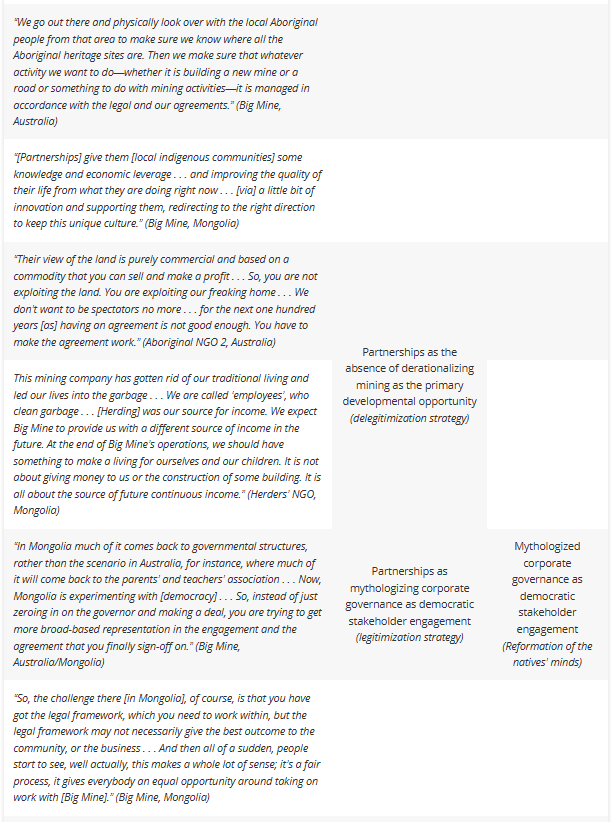

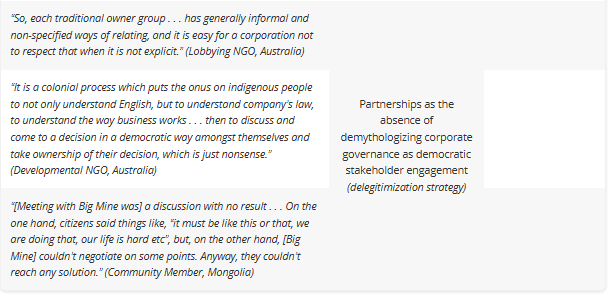

Table 3 presents the first-order illustrative quotes, second-order themes, and third-order aggregate categories.

Findings

Normalized Land Exploitation

Partnerships as Normalizing Land Exploitation

Big Mine dominates the physical space in both Australia and Mongolia by normalizing land exploitation there. Big Mine has displaced Indigenous communities from their traditional lands yet has justified irreversible economic, environmental, and social damages from this displacement as inevitable because mining itself is economically inevitable for the modern society that cannot stop consuming mineral commodities for its living and hence cannot stop exploiting lands with minerals. Mining partnerships, in turn, can only minimize these damages but never eradicate them, thus further normalizing land exploitation.

In Australia, before mining displaced Aboriginal communities from their land in the researched region, they had been already displaced by Anglo-Saxon farming and agriculture. The mining industry worsened their situation by relocating them to even further areas when the mining exploitation of the region began in the 1960s. This relocation not only confined them from being economically active in the researched region through such work as domestic house cleaning or service work but also negatively impacted their environment and culture.

According to Big Mine’s manager of agreements and economic participation in Australia, when “mining came to the [region], and people were no longer close to the mines, they were actually separated by quite a large distance. Their capacity to run businesses that service the mines or get employed at the mines was small because the distance was too large to travel. Miners brought money, alcohol, and a whole bunch of social problems to those communities, particularly during the construction phase” (CD, Middle-Level Manager of Agreements and Economic Participations, Big Mine, Australia, Interview in September 2016).

Four decades after Big Mine began land exploitation of the researched region in Australia, Mongolia became an attractive investment for Western mining multinationals, including Big Mine, which entered a joint venture with the Mongolian government and the mining company X that began the exploration of Project Y in the researched mining region. The area around Project Y overlayed traditional pasture and water sources of several households, whose traditional economic livelihood consisted of nomadic herding of goats, sheep, cattle, horses, and camels. As a result, these households have been resettled from within Project Y’s 10 km exclusion zone.

After displacing the local herder households to get access to Project Y’s mineral deposits, Big Mine diverted the local river. The diversion has resulted in the drying of multiple water wells used by local herders for their livestock. According to Big Mine’s community specialist in Mongolia, diverting the river “was absolutely necessary to save the river. Otherwise, the open river expands, and the river would be destroyed” (AQ, Lower-Level Community Specialist, Big Mine, Mongolia, Interview in August 2015). As a quick fix for this environmental damage, Big Mine constructed handmade wells for animals (e.g., camels). Yet, many of those wells were poorly designed and dried up soon after they were dug. A photo taken and provided by the director of the herders’ NGO (see Figure 1) illustrates camels drinking from handmade wells constructed by Big Mine in Mongolia.

While recognizing that any destruction of nature by mining is wrong for Indigenous communities, Big Mine, as its manager of heritage advising in Australia said, will not stop mining because “we are not going to stop building houses, running electricity, and expecting everyone to live in those conditions.” Since Big Mine, like other mining corporations, operates for the here and now—for profit—they do not really manage long term, apart from thinking, “Well, where are we going to get our next mine from?” (UR, Middle-Level Manager of Heritage Advising, Big Mine, Australia, Interview in September 2016).

Big Mine’s partnerships with Indigenous communities, therefore, can only aim to mitigate the negatives and maximize the positives of mining, as, according to Big Mine’s community relations director in Australia, Big Mine is:

never going to erode or eradicate the negative because [it is] a normal mining company that digs great big holes in the ground. The reality is that it is just the business we operate in, but the fact that it supports community practitioners to try and get that balance right and do the least amount of damage is a positive thing. (II, Middle-Level Community Relations Director, Australia, Interview in September 2016)

Partnerships as the Absence of Derationalizing Mining as the Primary Developmental Opportunity

Australian and Mongolian Indigenous communities and NGOs representing and advocating for these communities, however, argue that mining corporations are granted a de facto legal clearance to sterilize the lands traditionally occupied by these communities. While in both researched regions, there are laws requiring mining corporations to sign partnerships outlining their contributions from mining for local communities, these laws do not enable these communities to fully stop land exploitation as something that is not normal. National and regional governments, in turn, have taken a hands-off position in mining partnerships as they do not want to miss the economic opportunities that mining offers (“What if mining corporations leave the region?”), thus further perpetuating the absence of denormalizing land exploitation.

In Australia, for example, the Native Title Act, which establishes mining partnerships (i.e., land use agreements) as voluntary agreements between native title groups and other parties (e.g., mining corporations) about the social and environmental impacts on these groups, factually disempowers and discriminates against Aboriginal communities. According to the chief executive officer (CEO) of the Australian Aboriginal NGO that negotiated the researched land use agreement with Big Mine:

it is nowhere the intention of what Eddie Mabo3 set out to achieve when he fought for land rights. And you take the Aboriginal Heritage Act, which is also a discriminatory act against Aboriginal people. They are all designed to give miners and developers the key to the kingdom. I describe the law as a process that is designed to take our land away legally. (XZ, CEO, Aboriginal NGO 2, Australia, Interview in September 2016)

A CEO of another Australian Aboriginal NGO that was involved in the negotiation of the land use agreement with Big Mine mentioned that “if you said to the Aboriginal people or the group, ‘You got a choice to have mining and not to have mining,’ the majority will say, ‘Don’t have mining’” (UT, CEO, Aboriginal NGO 1, Australia, Interview in September 2016). Yet, Big Mine would not stop “sterilizing the country” should they have a choice, even if a 40,000-year-old Aboriginal cave can be destroyed in the process of mining, as The Right to Negotiate established in the Native Title Act does not allow Aboriginal people to stop a mining development that may damage their environment and culture.

In Mongolia, Big Mine and other mining corporations in the researched region have been granted legal control of grasslands and pasturelands that have been traditionally used by local herders. Historically, in Mongolia, land has not been owned by herders but has belonged to the state. When the resettlement program began in the researched region to vacate the land for Big Mine, local herders were offered to sign a three-party relocation agreement between the herders, the local government authorities, and the company X. Yet, as the director of the Mongolian herders’ NGO mentioned, herders were forced out of their herding regions without prior informed consent. The company X “preferred to have it signed by older people. For example, [a] 85-year-old [woman] . . . they [local governor and the company X] said to her, ‘grandma, sign here’ . . . This contract was confidential . . . They brought trucks and said, the longer you stay here, the more money you will pay. Under such pressure, we moved . . . When I was a herdsman, I had 600 sheep, about 30 horses, 100 camels, 20 cows . . . Now I have ten camels. I don’t have a pasture.” (KB, Director, Herders’ NGO, Mongolia, Interview in August 2015)

Then, as required by the 2006 Mongolian Minerals Law, Big Mine formed a mining partnership (i.e., Cooperation Agreement) with the local government authorities of the mining town and region where this mining town is located. This agreement outlined Big Mine’s contributions to local employment and other benefits for the local community, including local community programs and projects around the environment, cultural heritage, tourism, local business development, and procurement. Yet, unlike in Australia, Indigenous communities in Mongolia (i.e., herders) have not directly participated in the development of this agreement.

Rationalized Mining as the Primary Developmental Opportunity

Partnerships as Rationalizing Mining as the Primary Developmental Opportunity

Big Mine has incorporated local economic histories into the Western perspective by rationalizing mining as the primary developmental opportunity in both Australia and Mongolia. Big Mine views Indigenous communities’ traditional livelihood, including traditional occupations and artwork (e.g., Aboriginal hunting, stone painting and arrangements in Australia, herding, and stone sculptures in Mongolia) as not a viable alternative to mining but somewhat an artifact. Mining partnerships, in turn, can protect this artifact while further rationalizing developmental opportunities from mining (i.e., employment) as primary.

Big Mine sees itself as a development agent that creates significant value for regional and national economies. Lands traditionally occupied by Indigenous communities are, therefore, seen as having no economic value until their minerals are extracted and marketed by Big Mine in the relevant commodity markets. Those who criticize Big Mine and oppose mining, therefore, must have an anti-development sentiment. For example, according to Big Mine’s former top-level community manager and global expert in community engagement and social performance in Australia and Mongolia:

Everyone wants to believe that the resources on the ground are part of the national estate, so when you invite a foreign mining company in, it is like they are coming to plunder your treasury . . . A lot of Mongolians and people elsewhere think that the value of the company is the rock in the ground, but no, the rock in the ground has got no value whatsoever until you get it out . . . Life [in Mongolia] has changed really dramatically: ten years ago, people would have all been on horseback with a few Russian Jeeps, but now, a huge number of quite modern, well, very modern four-wheel drives, SUVs, and people are a lot more mobile . . . I just shake my head at the nonsense that goes on through it being a catalysing focal point for people’s anti-development sentiment. (NT, Former Top-Level Community Manager and Global Expert in Community Engagement and Social Performance, Big Mine, Australia/Mongolia, Interview in June 2015)

In Australia, Big Mine’s Land Use Agreement allows for conducting Aboriginal heritage surveys and talking to the local Aboriginal groups about its future mining development and the benefits this development can bring (e.g., employment). As Big Mine’s manager of cultural heritage in Australia commented, Big Mine:

go[es] out there and physically look[s] over with the local Aboriginal people from that area to make sure we know where all the Aboriginal heritage sites are. Then we make sure that whatever activity we want to do—whether it is building a new mine or a road or something to do with mining activities—it is managed in accordance with the legal and our agreements . . . We don’t just stop there and, “Okay, that’s all we want to talk to you about. You’ve been getting some benefits from us; leave us alone.” No, we keep engaging with them . . . to let them know what’s going on, let them know what other benefits there are that can come to them from our operations, whether that’s employment or that’s business development, that sort of things. (GM, Middle-Level Manager of Cultural Heritage, Big Mine, Australia, Interview in September 2016)

In Mongolia, Big Mine’s Cooperation Agreement is seen as a strategic framework that allows for supporting the sustainable livelihood and development of herders, thus providing mechanisms for their better co-existence with Big Mine during and after the closure of Project Y. For example, Big Mine’s manager of social performance in Mongolia emphasized that Big Mine can partner with local herders’ communities to keep and transfer the local nomad culture, which had not changed significantly in the last 100 years (e.g., ger accommodation and livelihood), to the next generations by:

giv[ing] them some knowledge and economic leverage . . . and improving the quality of their life from what they are doing right now . . . [via] a little bit of innovation and supporting them, redirecting to the right direction to keep this unique culture . . . Of course, our main business is mining. Like we bring more economic benefit, more value through our business to the shareholders and the government of Mongolia. So, it means, like, at the same time, we are being a responsible company, socially responsible company, in providing support to the communities. (SB, Middle-Level Manager of Social Performance, Big Mine, Mongolia, Interview in August 2015)

Partnerships as the Absence of Derationalizing Mining as The Primary Developmental Opportunity

Australian and Mongolian Indigenous communities and NGOs representing and advocating for these communities, by contrast, view the lands with minerals not as a commodity but as their home, which have been providing them and their ancestors with the sources of traditional livelihood. Big Mine and other mining corporations, however, have deprived Indigenous communities of other traditional sources for economic development, leaving them with mining rationalized as the major source of income or even a change of income in the future and mining partnerships as an opportunity to secure such future. National and regional governments, in turn, have taken a hands-off position in mining partnerships as they have a direct economic interest in mining (“What taxes can we impose on mining corporations?”), thus further perpetuating the absence of derationalizing mining as the primary developmental opportunity.

In Australia, for example, a CEO of the Australian Aboriginal NGO that negotiated the researched Land Use Agreement with Big Mine said that Big Mine and Indigenous communities live in two different worlds and, hence, their relationship is like “between a bird and a fish”:

Mining companies see our land only as a commodity . . . “Your land was nothing before we came here, and now it is valued because we found this resource and now, we have developed it,” and so on and so forth. But to us, we say, “Well, we never saw it as a commodity. We always saw it as our home, a home where we feel comfortable, a home where it shelters us, a home where it fed us, a home where it gave us our identity, a home where we grew our kids up, a home where our ancestors are buried, a home where people are born.” So, it has a socially significant value, a cultural value . . . Their view of the land is purely commercial and based on a commodity that you can sell and make a profit . . . So, you are not exploiting the land. You are exploiting our freaking home. (XZ, CEO, Aboriginal NGO 2, Australia, Interview in September 2016)

The Land Use Agreement with Big Mine, nevertheless, this CEO continues, can provide a source for Indigenous communities from being mere “spectators” of how Big Mine and other mining corporations “explore their country and make billions of dollars in the process,” as it has been in the last 40 or even 50 years, to becoming economically “self-sustainable” communities, who:

have to be right at the front of the gate and need to alongside [Big Mine] when [it is] continuing to develop [its]operations . . . for the next one hundred years [as] having an agreement is not good enough. You have to make the agreement work.

This agreement is, however, something that the regional government stays away from as it has “a conflict of interest and a peculiar interest [in mining] as well.”

In Mongolia, Indigenous communities consider partnerships with Big Mine as an opportunity to obtain professional and business skills and capabilities in areas that are not necessarily directly related to mining so that Mongolian ex-herders can replace herding with new occupations without being limited to occupations in mining. Big Mine has deprived these communities of their traditional livelihood and offered them and their future generations predominantly low-skilled employment opportunities in mining, as the director of the Mongolian herders’ NGO that filed a formal complaint against Big Mine to the international financial organization, which co-financed Project Y, said:

This mining company has gotten rid of our traditional living and led our lives into the garbage . . . We are called “employees,” who clean garbage. Our living is close to that of homeless people . . . They [Big Mine] provide a workplace, but they never teach, give advanced training . . . These people [ex-herders] never get to the promotion and stay coal-heavers, guards, and janitors for the rest of their lives. That’s their workplace. They [Big Mine] never think about us like, “Poor guys, I destroyed their livelihood, so I’ll train them if they won’t work in our mine, they can work somewhere else with that profession” . . . [Herding] was our source of income. We expect Big Mine to provide us with a different source of income in the future. At the end of Big Mine’s operations, we should have something to make a living for ourselves and our children. It is not about giving money to us or the construction of some building. It is all about the source of future continuous income. (KB, Director, Herders’ NGO, Mongolia, Interview in August 2015)

However, the national government, for instance, did not assist Mongolian herders in their requests for Big Mine to build a 40-km-long road to the soum4 center located near the mining site, while it permitted Big Mine to build a longer mine road from Mongolia to China.

Mythologized Corporate Governance as Democratic Stakeholder Engagement

Partnerships as Mythologizing Corporate Governance as Democratic Stakeholder Engagement

Big Mine has reformatted the natives’ minds by mythologizing corporate governance as democratic stakeholder engagement in both Australia and Mongolia. Big Mine perceives its governance of mining partnerships as a best practice of democratic stakeholder engagement, which is based on the practices of broad consulting and informing Indigenous communities, thus being a better alternative to regional or national legal regulations that do not assume such practices. Big Mine’s narrative is that this best practice is shared across its businesses globally yet cannot be applied universally as it needs to be democratically adapted to the cultural contexts of different regions and countries.

Thus, while in Australia, there is already a formed democratic society with a broad system of community representatives, in Mongolia, the process of forming such a system has only begun. According to Big Mine’s former top-level community manager and global expert in community engagement and social performance in Australia and Mongolia, Big Mine, therefore, had to institutionally “position itself” in Mongolia in such a way that it could adapt its democratic deliberation of mining partnerships it usually adopts in other countries like Australia:

In Mongolia, much of it comes back to governmental structures, rather than the scenario in Australia, for instance, where much of it will come back to the parents’ and teachers’ association: if you are talking about education, then you would talk to the parents’ and teachers’ association as much as you would talk to the education department. So, figuring all that out and then trying to avoid the temptation of just dealing with the governor of the province . . . Now, Mongolia is experimenting with [democracy], and many of the young people in Mongolia truly want democracy, by which they mean broad-based representation across a range of issues. So, instead of just zeroing in on the governor and making a deal, you are trying to get more broad-based representation in the engagement and the agreement that you finally sign off on. (NT, Former Top-Level Community Manager and Global Expert in Community Engagement and Social Performance, Big Mine, Australia/Mongolia, Interview in June 2015)

In Australia, however, there is a lack of legislation that would outline performative targets for mining partnerships. Regional legislative bodies avoid introducing such legislation because they do not have the necessary skills and capabilities to regulate corporate stakeholder engagement, which is ever-changing in its nature. Instead of prescriptive laws that would force mining corporations into box-ticking approaches, whereby they would only meet a bare legal minimum, Australian legislators prefer mining corporations to adhere to their own best practice standards.

In Mongolia, Big Mine influenced the national government to adopt Big Mine’s global partnership standard as a new national best practice. According to this standard, Big Mine establishes trusts that are managed independently and allocate funds to be used for the mining impact mitigation and community development programs, which are raised by the local communities’ members and get assessed by this trust’s board against the trust’s priorities. In Mongolia, however, there was no law regulating such trusts, and, according to Big Mine’s manager for health, safety, environment, community, and security:

the legislation is not necessarily best practice. And some of the things from a legal point of view actually do not make sense . . . So, the challenge there, of course, is that you have got the legal framework, which you need to work within, but the legal framework may not necessarily give the best outcome to the community, or the business.

It was, therefore, a challenge for Big Mine to “work through” the Mongolian legislation by “actually changing [it] to make it current, to bring in best practice, and to help, to influence”:

Now, initially, you see people kicking—“Ah, we don’t do business like that,” blah blah blah, “This is Mongolia!” . . . And then all of a sudden, people start to see, well actually, this makes a whole lot of sense; it’s a fair process, it gives everybody an equal opportunity around taking on work with [Big Mine]. And because we’re such a large entity here in Mongolia, our ability to influence that kind of thing is huge, you know? And our CEO has regular contact with the Prime Minister. He’s in a position where he can influence and influence in a really, really, really positive way. Which I think is great! You know, to be part of helping a country to move forward . . . What a great experience! (YR, Middle-Level Community Manage for Health, Safety, Environment, Community and Security, Big Mine, Mongolia, Interview in August 2015)

Partnerships as the Absence of Demythologizing Corporate Governance as Democratic Stakeholder Engagement

Australian and Mongolian Indigenous communities and NGOs representing and advocating for these communities, on the contrary, perceive Big Mine’s governance of mining partnerships as a colonial practice of stakeholder engagement, whereby Big Mine expects Indigenous communities to deliberate mining partnerships in a way that assumes their knowledge of English and corporate standards yet ignores the unique, less observable, and nuanced nature of their community governance structures. National and regional governments, in turn, have taken a hands-off position in mining partnerships as they assist Indigenous communities in their deliberation with mining corporations only when it works for their election cycles (“Will it help us in the forthcoming election?”) thus further perpetuating the absence of demythologizing corporate governance as democratic stakeholder engagement.

In Australia, an advisor from an international NGO that lobbies Australian mining corporations, financial organizations, and government to ensure that people and nature come before profits said that Big Mine, like many other mining multinationals:

have their compliance and regulations, [which] are just frameworks that support the corporate governance of agencies. It is really easy for a big corporation that is multinational and that just happens to be based in a place not to recognise the nuanced nature of community governance structures. So, each traditional owner group, like each community, each group of people in Australia that co-exist, have generally informal and non-specified ways of relating, and it is easy for a corporation not to respect that when it is not explicit.

Big Mine does its “the right thing” by “speaking to the right people” in Indigenous communities. Yet, it does so by following “a formal structure that is placed over traditionally what’s a very informal way of operating,” which, according to this advisor, is dangerous as it kills the culture of Indigenous communities by “eroding the informal, traditional nature of that [Aboriginal] group’s way of relating to each other . . . It’s not intentional, but this is a very huge power dynamic” (GA, Advisor, Lobbying NGO, Australia, Interview in September 2016).

Another advisor of an Australian developmental NGO that works with mining corporations to create socioeconomic opportunities in remote areas echoes the above perspective by saying that Big Mine has a “neoliberal sort of vantage point, or perspective that doesn’t understand what Indigenous groups want or need,” and, as a result, many important needs of Indigenous communities do not get negotiated and then realized in mining partnerships:

If you ask a [Aboriginal] person one day, “What did you like about that trip?” If I asked you that question, you would start getting a whole lot of things from your head, and you’d list 10 or 15 things and talk about them. They’ll only say one, and that’s what they think they’re being asked. They think they’re being asked, “Pick one thing.” (EX, Advisor, Developmental NGO, Australia, Interview in September 2016)

Mining partnerships negotiation, he continued, is a,

colonial process which . . . puts the onus on Indigenous people to not only understand English but to understand company’s law, to understand the way business works, to understand all these things that really require you to be an educated person and all that speaks for in the Western sense in order to master; then to discuss and come to a decision in a democratic way amongst themselves and take ownership of their decision, which is just nonsense . . . Everyone is trying to fit a square peg in a round hole . . . NGOs only want them [partnerships] if they’re not going to have to sell their soul in order to do it. The government only wants them if there are going to be results within their election cycle. Companies only want them if they’re going to be good for business.

In Mongolia, for example, such a democratic negotiation of the cooperation agreement resulted in Indigenous communities’ voices was not properly heard and considered by Big Mine. Before this partnership was signed, Big Mine initiated a broad-based meeting with representatives of the local community, which was attended even by the newly elected President of Mongolia. While community members, including local herders, raised a lot of concerns at that meeting, Big Mine’s decision-making after it “listened” to those concerns was nonetheless ineffective. As a community member who had been present at that meeting commented, it was “a discussion with no result . . . On one hand, citizens said things like, ‘It must be like this or that, we are doing that, our life is hard etc.,’ but, on the other hand, [Big Mine] couldn’t negotiate on some points. Anyway, they couldn’t reach any solution” (EI, Local Community Member, Mongolia. Interview in August 2015).

Discussion

Neither Naïve Nor Fatalistic Engagement

Management scholars have long advocated for mining partnerships that meaningfully incorporate Indigenous perspectives (Bastien et al., 2023; Derry, 2012; Newenham-Kahindi, 2011; Salmon et al., 2023). However, a gap remained in understanding the colonial underpinnings that create power imbalances and divergent perspectives between corporations and Indigenous communities regarding these partnerships (Banerjee, 2000, 2022; Banerjee et al., 2021; Maher, 2019; Ramirez et al., 2023). This study fills this gap by explicating how a mining MNC and Indigenous communities in Australia and Mongolia (de)legitimize their partnerships, revealing the deeply embedded nature of these relationships within global neoliberal capitalist stakeholder colonialism.

This research critically examines mining partnerships as corporate stakeholder neo-colonial engagement practices that aim to reach a seemingly win-win consensus. However, this consensus is discursively coerced by a win-lose postcolonial social objectivity that mining corporations present as inevitable. The study contributes to organizational knowledge by revealing how these partnerships are not merely transactional agreements but are deeply entwined with historical and ongoing colonial practices that disembed Indigenous communities from their traditional ecological, economic, and cultural spheres (Banerjee, 2022).

Indigenous social objectivities, historically embedded in complex and relational experiences with the land (Murphy & Arenas, 2010; Sawyer & Gomez, 2008), are disrupted by the hegemonic power of stakeholder colonialism. This power is manifested in the “mutual collapse” (Mouffe, 1999) between mining corporations’ social objectivity of the inevitability of mining and their authority to legitimize this objectivity in partnerships. By coercing Indigenous communities into a social objectivity where the only alternative to mining with partnerships is mining without partnerships, stakeholder colonialism perpetuates a cycle of disempowerment and disembedding from traditional spheres.

Governments’ hands-off approach to mining partnerships further entrenches this dynamic, positioning corporations as the entities responsible for filling the void left by governmental non-intervention. This institutional context allows corporations to present their best practice mining partnerships as legitimate and morally sound, even though these practices often perpetuate the very power imbalances they purport to address. This study underscores that such partnerships are not genuine democratic engagements but are success-oriented bargains mistaken for legitimate outcomes.

This research advances organizational knowledge by demonstrating that CSR in the form of mining partnerships is an “empty signifier” (Zueva & Fairbrass, 2021) strategically endowed with specific meanings by powerful state and market actors. These actors aim to erase cultural antagonisms and hegemonize discourses, thereby further colonizing subaltern groups (Alamgir & Banerjee, 2019; Banerjee, 2022). The study reveals that the corporate legitimization of mining partnerships is designed to erase antagonistic Indigenous perspectives and reinforce a social objectivity where mining is seen as inevitable. Indigenous communities, even when they delegitimize mining partnerships, cannot opt out of this overarching social objectivity, which coerces them into a disembedded existence and sidelines their alternative social imaginaries.

Thus, mining partnerships persist not because they are rational, win-win outcomes of democratic deliberation (Kapelus, 2002; Yakovleva et al., 2023) but because Indigenous communities recognize the futility of resisting the “dominant discourse” (Foucault, 1981) of stakeholder colonialism, born from the win-lose inevitability of mining. Given that the signed mining partnerships in Mongolia and Australia are not viewed as legitimate by Indigenous communities and their NGOs, the hegemonic power of the mining corporation is constituted not by both coercion and consent (Gramsci, 1971) but rather by discursive coercion without consent (Guha, 1997). This situation indicates, first, a failure of the hegemonic power of stakeholder colonialism to fully establish itself, and second, a potential for subaltern resistance and counter-hegemonic struggles by Indigenous peoples seeking to challenge the existing power structures (Guha, 1997).

I, therefore, argue that while certainly mining partnerships with Indigenous communities cannot be naïvely labeled as win-win, labeling these partnerships as win-lose would limit Indigenous communities’ perceptions of their future, as it suggests a pre-determined, fatalistic outcome similar to their past experiences with colonialism. Instead, this study calls on Indigenous communities to focus on resistance strategies that challenge this fatality, leveraging the findings of this study to advocate for more meaningful and equitable partnerships.

Amid the climate crisis, the inevitability of mining as a “matter of concern” (Latour, 2004) must be critically addressed. That is why, this study not only “lifts the rugs from under the feet of the naïve believers” (Latour, 2004, p. 246) in win-win mining partnerships by pointing at their neo-colonial win-lose nature but also offers Indigenous communities and mining corporations potential arenas for better exercising their choices for improved partnerships.

The first arena is the organizational level, where managers, who are culturally sensitive, can incorporate Indigenous perspectives that challenge existing managerial views within their corporations. However, the study acknowledges the challenges of democratizing mining partnerships within for-profit corporations, as these environments are predictably hostile to genuine deliberation (Sabadoz & Singer, 2017), especially over land use and natural resource extraction, where power asymmetries arising from colonial and postcolonial relations have become a norm (Banerjee, 2022). Despite these challenges, certain departments or newly established ones with a focus on partnerships may serve as intra-organizational public spheres for more democratic deliberation.

Nevertheless, while a corporation as a whole may not be an ideal site for democratic deliberation, certain parts of it may hold more deliberative potential than others (Sabadoz & Singer, 2017). Therefore, managers in mining corporations that aim to establish meaningful partnerships incorporating Indigenous perspectives should identify which areas of their organizations are more conducive to deliberation. This could be a department focused on partnerships, another department not directly related to partnerships, or, perhaps, a new department that integrates perspectives from various parts of the organization, thereby creating an intra-organizational public sphere for the democratic deliberation of mining partnerships.

I, however, would also like to highlight that merely acknowledging Indigenous worldviews is insufficient; these perspectives must be meaningfully represented in corporate decision-making. To achieve this, I suggest the inclusion of Indigenous chairs, directors, and advisory boards (Driver & Thompson, 2002) within corporate governance structures. This could help filter Indigenous perspectives into corporate boardrooms—the organizational areas that promote certain amounts of constructive disagreement (Forbes & Milliken, 1999; Sabadoz & Singer, 2017)—where they can be more effectively deliberated, contributing to greater “democratic validity” (Sabadoz & Singer, 2017).

This study thus also contributes to the broader academic conversation on the importance of including Indigenous knowledge in cross-cultural co-management and decision-making processes. Indigenous knowledge, as research shows, offers significant benefits for corporations, including improved sustainable resource management practices, environmental stewardship, and enhanced community relations (Cannarella & Piccioni, 2011; Leduc, 2006; Mercer et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2015). This study demonstartes how Indigenous perspectives on mining partnerships can offer a social imaginary of an alternative social objectivity where mining is not seen as inevitable, and argues that reflexive corporations must incorporate this, although somewhat uncomfortable, social imaginary to enter a new, post-fossil fuel social objectivity as the leaders and not as the laggards.

To shift mining partnerships from a superficial conception of dialogue focused on consensus-seeking (Whelan, 2012) to a deeper form of dialogue that brings material and ideological conflicts between partners to the surface (Powell et al., 2018), it is not enough to merely include alternative Indigenous perspectives at the organizational level. New forms of intercultural understanding are needed—ones that go beyond simply incorporating differences and inequalities by accommodating conflict and dissent (Banerjee, 2022; Mouffe, 1999). This requires an institutional arena where Indigenous communities can establish a “conflictual consensus” (Mouffe, 1999) with mining corporations.

Given their perspectives on mining partnerships that challenge managerial viewpoints, Indigenous communities should not seek to eliminate or suppress potential conflicts with mining corporations. Instead, they should aim to establish a form of consensus that acknowledges and embraces these conflicts. Such a consensus in mining partnerships would be a step toward more deliberative disagreement. However, for this to be realized, the “institutional absences” (Villo & Turkina, 2023) perpetuating mining corporations’ stakeholder colonialism must first be addressed. As this study highlights, meanings and practices that denormalize land exploitation, derationalize mining as the primary developmental opportunity, and demythologize corporate governance as democratic stakeholder engagement must be institutionalized.

The institutionalization of these decolonizing meanings and practices, in turn, necessitates an active role for governments in transforming the status quo of global neoliberal capitalism (Özkazanç-Pan, 2019). This transformation challenges the philosophical assumptions that corporations have an apolitical, economically focused role in society, with minimal government intervention and regulation (Mäkinen & Kasanen, 2015). Instead, it envisions a different, more cooperative economic system, one that is epistemically grounded in multiple and diverse economic, social, and political imaginaries (Banerjee, 2022). Democratic deliberation in mining partnerships, thus, if it is ever possible, cannot be achieved solely through changes within the organizational arena; it also requires the necessary changes in the institutional arena.

Finally, it can be argued that by forming partnerships with “mediating” stakeholders (Banerjee, 2001; Calvano, 2008)—such as NGOs representing and advocating for Indigenous communities in Australia or local state authorities signing partnerships on behalf of these communities in Mongolia—mining corporations further marginalize Indigenous communities. This practice perpetuates stakeholder colonialism by deeming external entities more legitimate than the communities directly impacted by business activities (Smith, 1999). This dynamic not only reinforces existing power imbalances but also undermines the sovereignty and self-determination of Indigenous peoples (Alamgir & Banerjee, 2019; Banerjee, 2022). Therefore, the very concept of stakeholder warrants critical examination and requires decolonization by recognizing Indigenous communities as primary stakeholders with inherent rights to their lands and resources, rather than as secondary or represented interests. Such a shift necessitates a fundamental rethinking of stakeholder engagement practices, emphasizing the need for direct inclusion and genuine partnership with Indigenous communities in decision-making processes, as previously suggested.

Theoretical Generalization

Management scholars have suggested that comparative studies with the cases in countries such as Mongolia can help us to refine the understanding of various business and society phenomena, such as CSR, as these studies can unpack the embeddedness of these phenomena in the unique national institutional fabrics that are different from the Anglo-Saxon world traditionally researched by management scholars (Crane et al., 2016). By comparing two cases in Mongolia and Australia—the two countries that have postcolonial legacies and strategically important mining sectors—I expected that their unique national institutional fabrics would bring to light theoretically significant differences.